The X-ray View of the Cosmic Web

Relevant Works: Connor et al., 2018 Connor et al., 2019c

Cosmological simulations, from Klypin & Shandarin (1983) to Springel et al. (2005) and beyond, show that the Universe is made of thread-like structures, tying together the densest parts of the cosmos. Similar features were seen in large redshift surveys, from Jôeverr, Jaan, & Erik (1978) to the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. These filaments are an important reservoir of baryons in the Universe -- most of the missing baryons should be in warm-hot gas in these structures.

If filaments are full of gas, they should be visible to X-ray satellites. Briel & Henry (1995) went looking for filaments in the ROSAT All-Sky Survey, but found nothing -- and the next decade and a half was full of similar non-detections. It wasn't until the work of Werner et al. (2008) until a compelling detection of filaments between clusters was seen, and this was for the special case of two merging clusters, where the filament was seen mostly on-axis. Since 2008, there have been several more detections of X-ray filaments (e.g., Eckert et al., 2008, Alvarez et al., 2018), but, not to take anything away from those works, all have utilized the enhanced temperature and density of filaments around merging clusters.

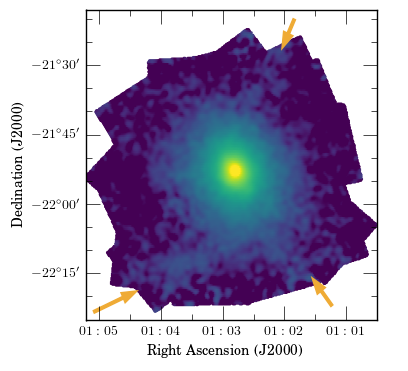

In Chandra Cycle 13, 2 Msec was awarded to observe

Abell 133, a relatively nearby cluster (z = 0.0559) out to

and slightly beyond the virial radius.

While this program was intended to study the virilization region,

upon removing point sources and clumps three large-scale structures

were visible (seen in the image on the right).

These were believed to be filaments of the Cosmic Web

seen in these deep images (Vikhlinin

2013). If true, this would be a significant result, not

just for the analysis of these filaments, but also for the potential

for future X-ray satellites to perform similar observations of a large

number of clusters. But, soon after the announcement of these

results, another study by

Morandi & Cui (2014) on the same data was released, and they did

not detect the same structures. Obviously, an independent measurement

was needed to clarify the situation.

In Chandra Cycle 13, 2 Msec was awarded to observe

Abell 133, a relatively nearby cluster (z = 0.0559) out to

and slightly beyond the virial radius.

While this program was intended to study the virilization region,

upon removing point sources and clumps three large-scale structures

were visible (seen in the image on the right).

These were believed to be filaments of the Cosmic Web

seen in these deep images (Vikhlinin

2013). If true, this would be a significant result, not

just for the analysis of these filaments, but also for the potential

for future X-ray satellites to perform similar observations of a large

number of clusters. But, soon after the announcement of these

results, another study by

Morandi & Cui (2014) on the same data was released, and they did

not detect the same structures. Obviously, an independent measurement

was needed to clarify the situation.

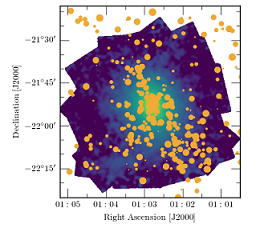

This is where we come in. Using the IMACS spectrograph on the Baade Magellan

telescope, we conducted a spectroscopic survey of over 3,000 galaxies in and

around the X-ray field of view. This 4 year campaign, in combination with

archival redshift surveys (6DF;

NFPS;

Way,

Quintana, & Infante, 1997), gave us a catalog of around 300

spectroscopically-confirmed cluster members. The distribution of these

galaxies can be seen in the image to the left. As an added bonus of this

survey, we were able to better constrain the kinematic state of the cluster;

evidence of an ongoing-merger reported by prior works was not seen under

deeper scrutiny.

This is where we come in. Using the IMACS spectrograph on the Baade Magellan

telescope, we conducted a spectroscopic survey of over 3,000 galaxies in and

around the X-ray field of view. This 4 year campaign, in combination with

archival redshift surveys (6DF;

NFPS;

Way,

Quintana, & Infante, 1997), gave us a catalog of around 300

spectroscopically-confirmed cluster members. The distribution of these

galaxies can be seen in the image to the left. As an added bonus of this

survey, we were able to better constrain the kinematic state of the cluster;

evidence of an ongoing-merger reported by prior works was not seen under

deeper scrutiny.

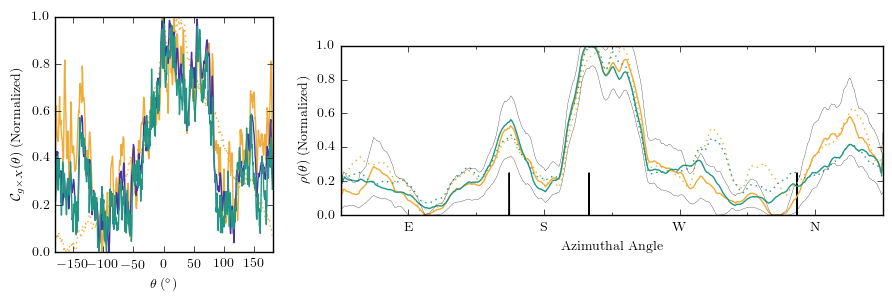

The comparison between the distribution of the galaxies and the detected X-ray

structure is shown in the image to the right. On the left, we show the

cross-correlation between the X-ray emission and the galaxy emission;

it peaks at 0 degrees -- that is, when rotating the galaxies around a

fixed center, they show the strongest ties to the X-rays at their observed

position. The right image is a measure of the angular density for the galaxies;

this peaks at the positions of the two southern filaments (shown by vertical bars),

but the northern structure does not exactly align with the observed filament.

Nevertheless, the significance of the connection between the galaxies and X-rays

is roughly 5-sigma.

The comparison between the distribution of the galaxies and the detected X-ray

structure is shown in the image to the right. On the left, we show the

cross-correlation between the X-ray emission and the galaxy emission;

it peaks at 0 degrees -- that is, when rotating the galaxies around a

fixed center, they show the strongest ties to the X-rays at their observed

position. The right image is a measure of the angular density for the galaxies;

this peaks at the positions of the two southern filaments (shown by vertical bars),

but the northern structure does not exactly align with the observed filament.

Nevertheless, the significance of the connection between the galaxies and X-rays

is roughly 5-sigma.

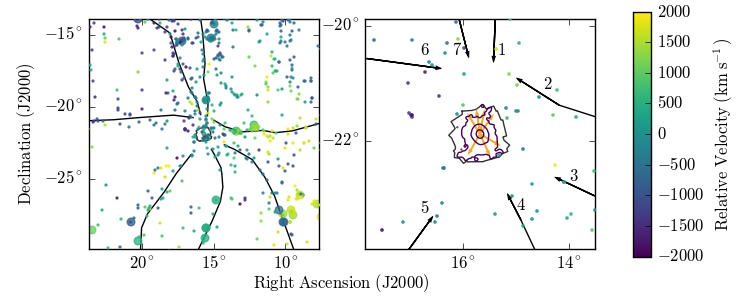

One of the assumptions of the analysis so far is that the detected

filaments connect to the Cosmic Web; if that's true, than we should expect to see

large scale structure connecting to the cluster at around where the

X-ray filaments are. Using the large field covered by the 6DF, we

identified all possible filaments that could be connecting to Abell

133. These are shown in the figure to the right. Their connection

points all align with the directions seen in the X-ray image. This

is further compelling evidence that we are actually seeing evidence

of cosmic filaments connecting to a cluster.

One of the assumptions of the analysis so far is that the detected

filaments connect to the Cosmic Web; if that's true, than we should expect to see

large scale structure connecting to the cluster at around where the

X-ray filaments are. Using the large field covered by the 6DF, we

identified all possible filaments that could be connecting to Abell

133. These are shown in the figure to the right. Their connection

points all align with the directions seen in the X-ray image. This

is further compelling evidence that we are actually seeing evidence

of cosmic filaments connecting to a cluster.

This isn't the end of things, of course. I am currently conducting a much deeper spectroscopic survey with IMACS, which will tie down the area where the cosmic and cluster filaments meet. Using better spectroscopic methods than the previous survey, we will be able to greatly expand our understanding of the area around Abell 133. In addition, I secured time on the Hubble Space Telescope to observe a nearby quasar with COS. This will give us an independent measure of the density of the gas at one filament sightline. Look for these results in the coming year!